Giedre Purvaneckiene

Member of Seimas of the

Republic of Lithuania

SOCIETY IN CHANGE – IS IT TIME FOR GENDER EQUALITY?

Since 1990s and

especially after 1995, when the IV UN Fourth World Conference on Women took

place in Beijing, in all spheres of life in countries with changing societies

positive changes towards status of women and equal gender opportunities are

noticeable. But at the same time, gender equality is not yet achieved in any

of these spheres. And processes according to my view slowed down, sometimes we

can notice even backlashes. I will illustrate these my statements using

examples mainly from Lithuania, the country regarded as one of the most

advanced in state policy in gender equality among the countries in transition.

A

deteriorated situation of women, their discrimination, unequal treatment of the

feminine and masculine gender, as well as stereotypes of gender roles confirmed

by opinion polls justify the requirements to improve the situation raised by

women organisations. As a result of that, legislation has been amended, a

mechanism for the implementation of equal opportunities is in the pipeline,

women progress programmes and programmes for the implementation of equal

opportunities are being drafted and applied. All of these processes are

intertwined with tremendous social transformations. The public at large has

achieved a huge headway towards democracy, free market is firmly established in

the economy, private initiative has developed. These changes were accompanied

by unemployment, poverty, and stratification of the society. The index of

differences in the income level puts Lithuania among the countries with a

relatively great inequality. As a result of that, a new phenomenon emerged –

feminisation of poverty. Poverty usually affects households of widows and

divorced women with children.

Numerous changes

in the society are associated with ignorance of gender specifics: the

consequences of the decline in the number of kindergartens, in fact, affected

only women. Women were the ones who faced most difficulties in participating in

paid employment and public activities. There are more cases of this type, and

often they promote poverty feminisation.

Let us briefly

overview changes in the gender situation in the light of social transformations.

Women’s level of education is higher than that of men, and the educational gap

between men and women is growing. The highest level of secondary schools as

well as colleges and universities are attended by more girls than boys. In

2001, women accounted for 59 per cent of the total number of University

graduates with Bachelor’s degree and 60 per cent of those awarded Master’s

degree. The labour market, too, experiences positive changes: the share of

unemployed women in 2001 was lower than that of men. Though on average, women

earn less than men, the salary gap between men and women is narrowing both in

the public and private sectors. Statistics bears witness to that. Nonetheless,

a more in-depth analysis is needed. What influence is made on this statistics

by the shadow economy and existence of unofficial wages? In 2001, women made up

64.8 per cent of people employed in the public service, and their average

salary equalled to 76.8 per cent of the men’s salary. The private sector

employed 43.1 per cent of all women, and their salary made up 83.3 per cent.

The data on the salary level in the public sector are reliable, beyond any

doubt. And what about the private sector?

The two areas

that are least favourable to women are politics and violence against a person.

The fact that they are unfavourable is proven by factual data. Two fifths of

women suffer from domestic violence, and the residual effects of violence

reduce women’s capabilities to be equal members of the society. No essential

changes, however, have been reached in the area of violence eradication. The

main obstacles to change this situation are prevailing views, while in the area

of violence, laws, as well.

Even when the

participation of women in politics was at its peak, their involvement did not

reach the level of “critical mass” either in local governments or in the

Parliament and Government. Presently, when f our members have left the

Parliament, women account only for 10.2 per cent. It should be noted that in

all countries in transition around the Baltic Sea, women in Parliaments do not

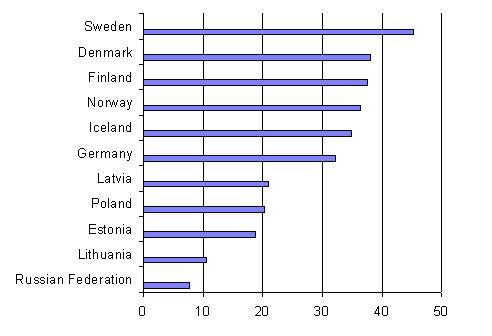

reach the critical mass (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Women in Parliaments of the Baltic Sea Region, %

(as of 28 March, 2003)

Though value

orientations, and gender role expectations of the Lithuanian population have

been changing and modernising in the recent decade, they still remain

patriarchal in their nature. The opinion of the Lithuanian people, including

women, about women’s involvement in politics has not changed at all.

Lithuanians remain absolutely indifferent to women’s participation in politics

and governance. By the way, the traditional division of roles in the everyday

life of a family has become yet stronger in the period between 1994 and 2000.

A new phenomenon

emerged in the latter years: state policy of equal opportunities. It develops

in along three lines. In 1994, the creation of National machinery for the

advancement of women started, the development of which was determined by the

change of the Government. At the end of 1997, the state policy was focused on

the enforcement of equal opportunities. Two positions of staff directly

responsible for the implementation of equal opportunities were established in

the Labour Market and Equal Opportunities Department of the Ministry of Social

Security and Labour, while the Department of Statistics set up a position of

staff responsible for gender statistics. The Government has set up a Commission

for Equal Opportunities of Men and Women, which comprises representatives of

all ministries, the Europe Department and the Department of Statistics. In

September 2002, the post of an adviser to the Prime Minister was

re-established.

At the end of

1995, the Government approved the Action Program for the Advancement of Women.

In 1997, the new Cabinet reaffirmed its support to the programme, approved the

action plan for its implementation, and earmarked funds for certain programmes

and actions. The Action Program for the Advancement of Women was implemented by

the Government in collaboration with NGOs. Due to the change of Governments,

the implementation and financing of the programme have been delayed for some

time. Presently, the process of approval of a newly drafted Plan for the

Implementation of Equal Opportunities of Men and Women has set off in the

Government. Attempts are made to mainstream gender aspect into all state

policies.

The third line of

action consists of the control of equal opportunities. The Seimas adopted a Law

on Equal Opportunities on 1 December 1998. In spring 1999, an Equal

Opportunities Ombudsman was appointed and a relevant office opened.

Unfortunately, on 27 February 2003, when drafts of the Seimas Resolution on the

Approval of the Regulations of the Equal Opportunities Ombudsman were submitted

for the parliament, the implementation of the Equal Opportunities Law as well

as the existence of the Equal Opportunities Ombudsman Office were put in

jeopardy.

What conclusions

could be drawn from the brief overview of the changes in social gender

differences? It has to be admitted that no major progress has been achieved in

the elimination of social gender differences, moreover, the results achieved

are not stable. For instance, in 1996, the number of women elected to the

Seimas increased considerably, however, that was determined not by the change of

the system of values or views, but rather by other causes. This is why in 2000

we went back to the beginning of the 20th century according to the

share of women elected to the Parliament.

What are the main

causes behind the instability of changes in gender differences and relations? I

think, one of the most important causes is the fact that the transition from

the advancement of women policy to equal opportunities policy led to the

strengthening of the gender neutrality principle. This is particularly true of

legislation. Amendments to laws regulating various fields of life left out

discriminatory rules in terms of gender as well as most safeguards provided for

due to biological functions of women. Nonetheless, the introduction of gender

dimension into the analysis of social processes and social policies in no way

means that laws and other pieces of legislation must retain gender neutrality.

The integration of the gender dimension means that consideration is given to

cultural and social gender differences, and analysis is made of all political

instruments or laws influencing both genders in a specific country. For

example, the New Criminal Procedure Code, as well as the one valid at the

moment, pays absolutely no attention to gender differences in cases of violence

against a person. A different procedure is still applied for the cases when the

perpetrator of violence is a family member and when he/she is a stranger. The

Criminal Procedure Code is much more lenient in the cases when violence is

perpetrated by a stranger. What has gender difference to do with this? The

thing is that usually the victims of domestic violence are women, children, and

in very rare cases men. While physical violence perpetrated by strangers more

often affects men. The gender neutrality, however, is retained. In both cases,

the provisions of the law treat women and men equally. But it is only women who

are victims of domestic violence…

Another

example is taken from Part III of the Civil Code “Family Law”. The provision of

Article 3.69 (2) of the new code can be quoted as a classical example of

applying the gender neutrality principle: “If one spouse is guilty of the

termination of marriage, the court can, upon the request of the other spouse,

prohibit the spouse guilty of dissolving marriage from retaining the surname

obtained in the marriage, except for the cases when the spouses have common

children”. There are no doubts that this provision is applied to both genders

equally. However, only 0.6 to 0.8 per cent of married men assume the surname of

their spouse. This case is a perfect illustration of total disregard of

cultural traditions as well as public opinion. It is only in Lithuania that the

surname of a woman reflects her marital status. On the other hand, the negative

approach of the public towards “old spinsters” is well known. Therefore, this

legal provision, which is still in effect, discriminates against women due to

the cultural tradition and due to its applicability to women only. These rules

are not the only ones that incorporate the principle of gender neutrality with

truly unfair implications to persons of different gender.

One may ask then: what are you, women in parliament, doing? But there are so few of us, our initiatives are not taken seriously, ridiculed by the mass media, men do resist, lawyers who comprise well paid group with conservative views, do resist. Very often any gender issues are not taken seriously (Box 1.)

|

Box 1. Extract from protocol of plenary session of Seimas (17 04 2003). Discussions on approving candidature of Equal Opportunities Ombudsman. Member of Seimas (male): Dear colleagues, I will support

the candidature, but I would like to spread experience for men who are

discriminated by wives at home. How I avoided this? I bought a tribune and

when my wife is complaining, I order her to speak from the tribune. And when

one has to go to tribune, then, you know, she has to be prepared. In one

word, we escape from unnecessary rub and mess. One has to buy a tribune. |

Who could perform

the gender-oriented analysis of all legislation and policies? Today probably

the only institution of this kind is the Equal Opportunities Office. They have

not done anything like that up to now – maybe they lacked willingness, maybe

capacities – it would be difficult to tell now. And now they face a threat of

being no longer able to do that in future.

Here I should

note that there is big differences in perception of gender equalities and equal

opportunities by the members of women’s NGO’s, and civil servants – equality workers,

including Equal Opportunities Ombudswoman (Box 2).

|

Box 2. Extract from protocol of plenary session of Seimas (17 04 2003). Discussions on approving candidature of Equal Opportunities Ombudsman. EOO (answering question on positive discrimination): …

Look now what is going on at the universities. Women comprise over 70% of

students (NB! in reality – 57.7%), may be some day it will

be necessary to apply positive discrimination towards men. Nobody says no.

... |

No real prospects

of changing the situation are seen for the time being. A feminine approach to

the management and administration of the society is not represented in politics

and government, and what is more, women themselves do not perceive the

necessity. Who will conduct gender-related analysis and monitoring of all

legislation, policies, programmes if there is no one to make decisions of this

kind? The Nordic countries have an asset in this respect, as they can carry out

an analysis of budget in terms of gender following a decision that has been

made by an almost similar number of woman and men. Against this background, I

would like to point out that organised movement of women includes far from

sufficient number of women to be able change the public opinion on gender

issues. The education system, which is one of the most important factors in the

socialisation of children and youth, keeps shaping patriarchal views. Research

into gender issues is scattered, not co-ordinated and not taken into account in

the decision-making. The research is scarcely linked to women NGOs that cannot

refer to scientific evidence in their activities unless the research was

carried out by themselves. I hope that this conference attended by scholars,

practitioners, politicians and public figures will push forward the consolidation

of the feminine gender.