Library is a keyword

political power through the public library

These notes relate to the roundtable discussion on Internet

and Copyright at the Finnish Institute in London, 9 October 1998.

1

I build

on nine points which I presented to the seminar of VECAM in Hourtin 27.8.98

as a part of the the discussion Quelle Europe? Vers un autre modèle

de societé. 2 Critique

and suggestions (including corrections of language, because English

is not my mother tongue) will be gratefully received and taken into account

while I continue to work on the (hyper)text. Send the comments to

book@kaapeli.fi or fax +358-9-27090369

- Mikael Böök.

1. Democracy and information form an inseparable couple

This is almost self-evident . The people needs the light of information. However, to be informed means to be a member of the reading public, to share written information. Modern democracy is based on literacy; it rests on the the printing press. (Most of the information broadcasted by radio and television, too, is based on the writing and the reading of written information.) The making of democracy has been a long revolution: it took our political systems ca four centuries after the advent of the printing press to reach this stage. For instance, only during the now ending twentieth century have women had the right to vote and the right to information. These two rights, too, are inseparable and the example of the womens' rights alone is a sufficient reminder about our democracy's young age.

Nowadays, our ways of writing, storing, distributing, and reading information are changing fast. So are our possibilities to own, control and free the information. What new conditions does digitalisation create, what strain does it put on democracy? Of course, this formulation of the question overstates the role of technology as a causal force in political history. Digitalisation does not come alone, so to speak; the ways in which the digital technology is spreading and being used today can only be understood in its interconnectedness with economy, society and politics. For example, the development and global diffusion of electronic information technology was, and is, both a cause and a consequence of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The rapid international penetration of the microcomputers and of internet during the nineties was “caused" by the world political events which we know as the “end of the Cold War". Yet (as the very example of the USSR goes to show) we must also take care not to underestimate the role of technology. Not only are information and democracy an inseparable couple; it is also reasonable to presume that a special relationship exists between information technology and democracy. It is already more than likely that the digitalisation of information marks an epochal shift in the political system. The digitalisation of information forces us to reflect on the young age and the incompleteness, but also on the fragility of democracy. This fragility is revealed precisely in matters concerning information, where democracy often rests on modus vivendi, i.e. on a more or less enduring balance of economic and social interests.

In a literal sense, democracy is a way of life (a modus vivendi).

It is political activity rather than a set of rules of political conduct.

Moreover, we should understand information as activity. Information is the

breathing, the political power of the people is the air. The critique of

the present information society starts from the insight that information

is inseparable from the human acts of feeling, understanding and knowing.

It must be based on a concept of information as meaning.

2. We may go to hell in a democratic way

Germany 1933 is a well-known example of how a society sometimes can proceed straight to dictatorship by election and parlamentarism. The present law-making about the information in the information society is another case, albeit a much less obvious case, of how we may go to hell in a formally democratic manner. I here think both of the national and the European and international efforts to shape (and “harmonise", as it is called within the EU) a new Intellectual Property Right which is better adapted to the digital environment than the traditional droit d'auteur (the right of the author) and freedom of information.

The issue is far too important to be delegated to the juridical specialists. In effect, who are specialists on information? If one starts from a concept of information as social meaning and leaves out the more or less esoterical context of the natural and engineering sciences, then three professional groups come to mind as potential candidates. First come the authors and artists, who are, literally, the creators of new social meaning. Secondly, the journalists, the professionals in the compilation and rapid communication of information, which is a category as difficult to define strictly as the authors. Third, the librarians who, guided by their vocational education and ethos, classify, store, retrieve and present the recorded information to the public according to more or less precise but extremely varied demands.

I shall argue that the the librarians, more than the other two groups, deserve to be called the specialists on information. (Actually, a particular group of librarians are titulated “information specialists", i.e. the librarians who specialise in information systems, databases and information retrieval.) The good physician must know many things and maintain many skills in order to be the doctor of the human body. Likewise, the good librarian has to integrate the information as meaning and information as atoms or bits into a the most generic and universal concept of information possible. Let the librarian be our doctor of information while the artistic or scientific creator plays the role of the pathbreaker (the innovator of concepts and methods) and the journalist takes care of the survival and well-being of the patient from one day to another.

With these remarks I certainly intend to pledge for an upgrading

of the profession of the librarian on the ranking-list of experts in (and

on) the “information society". Yet the Intellectual Property Rights

are, first and foremost, political issues. The ownership of information and

the limits to this ownership, the principle and specific rules of public

access, the moral rights of the author, the information rights of the individual

and of the public at large, and other related questions, are some of the

key questions we have to take stand to when we set out to decide about the

very “model" of the “information society" in which we and our children

intend to live. Therefore, the way we handle these questions is a crucial

test of democracy itself. The people is to decide about them, but how?

Recently, our (Finnish) Ministry of Education arranged a hearing about the draft EU Directive on the harmonization of copyright. About a hundred organisations were invited to give their opinion on the draft. Many of the groups realised that it was in their interests to respond to the call. So almost everybody was present and listened to. The Ministry will now try to take everybody into account. All of this looks very democratic indeed. Except that this was not really a public and political event at all, although, as a representative of the Library Association had the guts to say, there are some "political decisions about society" involved. But the speeches, statements and positions hardly touched upon politics; the discussion never took off from the economic and corporative phase of politics, the level of lobbying, group-interests, and specialists. The copyright specialists of the telecom firms expressed the interests of their economic sector. The creators of new information did not speak for themselves, in which case we would perhaps have heard several different, conflicting and fruitful thoughts. No, the authors and artists spoke through advocates, the copyright lawyers and the staff of the so called collecting societies. The representatives of libraries and museums defended their professional interests, and in so doing doing , they may also have done something to defend the interests of the public. Significantly, as a group, the journalists and media remained silent both during the hearing and afterwards. There was no public echo, no impact in wider circles, no feedback from the people. There was no true politics and therefore, in spite of so many positions being stated, the hearing was not democratic. Nevertheless, the event had the air of democratic decision-making. It was another example of going to hell, democratically.

The famous lobbying which is carried out in Brussels by all kind of organisations, and especially by the economically and politically strong industrial and commercial interests, is the "European" version of corporativism. According to well informed sources among responsible officials and mebers of the European parliament, hardly any international treaties and EU directives have been lobbied as intensely as the WIPO Treaty of Copyright (1966) and the draft EU Directive on the Harmonisation of Copyright (the draft of which was presented in December 1997). However, lobbying is merely a substitute to democratic ways of handling political questions and tasks. As it not so seldom happens that it produces the results which the lobbies are hoping for and is thus crowned by “success", the institutionalized lobbying helps to maintain the illusion that democracy is somehow functioning in Brussels or at other points of international decision-making.

But the rise of lobbying, now accepted in wide circles as

“politically correct", is only the symptom of a more serious disease.

The actual cancer of democracy is the concept of information, which has captured

the minds of the political and economic leaders of the present “information

society". At any seminar and hearing one can hear them use phrases like

“the content industry", which summarizes their idea of what information

is really about, namely, business. Of course, it cannot be denied that

information has long been and will remain an area of business. However, only

in the “information society" has the idea of information as merchandise

become the dominating concept. It has already come to be something of a dogma

that information should always be bought and sold but never shared. This

way of thinking is, of course, closely related to the view that a newspaper

or a television network is just a business and therefore, firstly and foremostly

responsible to its owners. The role of the journalistic media in society,

and their necessary political mission, has been subordinated to the corporative

and economic functions they may fulfil in the globalized “content industry".

Again, this takes place in a formally democratic manner. Mostly, the journalists

themselves sheepishly accept that the structure of the democratic public

sphere is demantled and sold away before our eyes. (Mr Arne Ruth, who resigned

from his post as the editor-in-chief of the Swedish newspaper “Dagens

Nyheter" in protest against the financial manipulations of the Nordic media

owners, is one of the few known exceptions to the miserable capitulation

of the “fourth state power" to the power of capital.)

3. The destiny of democracy is determined by the transformation of the public sphere.

The public sphere and the “reasoning public" itself is a sine qua non of democracy. The “reasoning public" is kept alive by the functioning of a number of well-known institutions: public places and locales of the city and the commune, cafés, restaurants, clubs, books, journals, newspapers, libraries, schools, radio, television and the internet. Obviously, these institutions, and their mutual interplay, are undergoing a structural transformation, to borrow the term of German sociologist J.Habermas in his study of the rise and development of the public sphere (Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit, 1962).

Habermas described and analysed the public sphere (“a category of the civil society") both as a necessary condition for and the life-environment of democracy. His book continues to transmit insights into the structural changes within the public sphere and how these may determine the fate of democracy. Habermas's approach has indeed only increased in importance during the subsequent decades after his book was published. It has been said that Habermas idealizes a certain type of “reasoning public", i.e. the eighteenth-century gentlemen who went to coffee houses to discuss politics and literature over the journals of the day. According to some critics, for Habermas the public sphere always in the end means a public house, or a physical place, where people can meet face-to-face like they are supposed to have met on the agora of ancient Athens. Habermas would therefore have failed to understand and appreciate implications and the possibilities of telecommunication via radio and television, not to speak of e-mail and the World Wide Web. This critique is not wholly justified, because the public sphere is also the sphere of the decision-making of society. Which vital decisions are (or can be) taken by the sole means of telecommunications, i.e. letters, telephone, radio, television or the Internet? In the end, face-to-face communication is needed whenever a group, or a society, is to take its decisions. The role of telecommunications in the actual decision-making may be more or less important, but it is not playing the first part.

Habermas still shows the right way even if the public sphere now may seem to have changed as much from the time he wrote his book about it as it had transformed during the whole period he described. It remains true that the destiny of democracy is determined by the transformation of the public sphere. Yet our attitude to the present metamorphosis should not be a repetition of the the cultural pessimism of Habermas in the 1960ies. Habermas was caught in the contrast between the democratic ideals of the classical liberal or socialist thinkers and the misery of “the reasoning public" in the age of mass-media and consumerism. It is as if he was standing on the ruins of the public sphere and, from there, telling us the long story of its decline. Without falling in the trap of technological utopianism, we should realise that the time has come to start building the public sphere anew with the building blocks and tools of today. Thus we must look at the habermasian “transformation", not as a process of the past, but as the challenge of the present and the task that lies ahead of us.

Today, it is a widely spread belief that the slogan the slogan

laissez-faire, laissez aller is a sufficient policy on the transformation

and reconstruction of the public sphere. This is naive and utopian, to say

the least (and on the assumption that it is not cynicism), although the general

ignorance of the nature of the changes is to some extent explained by the

stupefying tempo of the “digital revolution" of the 1990ies. Most

politicians and business leaders spontaneously prefer to see the information

technology as a means of economic competition rather than as a transformer

of politics and the cultural life. Hence their enthusiasm for the new technology,

which they hope will help their businesses, their countries or their European

Union to get by and succeed in the day-to-day economic struggle. Hence also

their lack of vision of the “information society".

4. The library is the loophole of the citizens

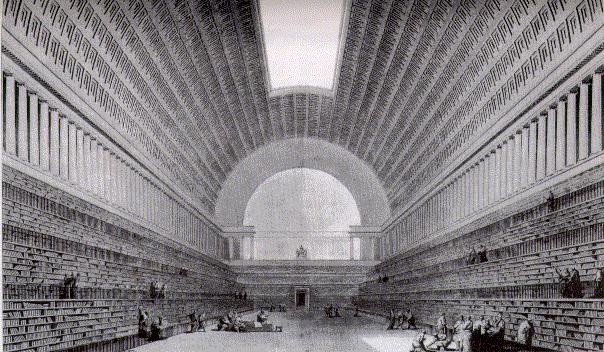

The drawing “Deuxième projet pour la Bibliothèque

du Roi", by Etienne-Louis Boullée, from 1785 shows a gigantic basilica,

capable of holding the memory of the whole

world.3 With this picture, the architect

has captured the dream of the complete library. But Boullée's drawing

is also a much-telling illustration of intellectual property and its relation

to democracy. Would his Majesty the King ever let the man from the street

into his private library?

The library is old as Egypt, but the public library is as young as democracy, and it is equally imperfect and incomplete. The public library is the loophole of the people into the realm of information, knowledge and royal entertainment. Our task is not to diminish that hole, but to do everything to widen it and make it more comfortable.

I caught a glimpse of the human comedy, an introduction to the essential things of life, by reading “Pappa Goriot" (Le Père Goriot) by Balzac. It must have been one of the first books I found when I started to frequent the Helsinki City library as a schoolboy. For many of us, the public library has been and is, perodically, a place as important as home, school or work-place, let alone the church. In Accra, too, while travelling in West Africa as a young student, I frequented the beautiful Gearge Padmore library to do research for some newspaper articles I wrote for the purpose of covering the travelling expenses.

What student can pursue the studies without access to the shelves and the reading-places of the libraries? I don't know how many hours I spent there with the text-books and monographies I could not have afforded to buy with my study-loans. Later on, there were times when I only went sporadically to the library, and other, intellectually and/or politically more active times when I used it intensely. For the individual, the library may be relatively unimportant in the short run, but it is clearly very important in the long run. Starting from my own experience as a library user, I think of the library as one of the vertebra of democracy. I use the library, therefore I am a citizen.

Which is the role of the public library in the transformation of the public sphere? Obviously, the library itself is subject to radical change. The concept of the digital library is enough to make anybody feel vertigo because, at first sight, the words 'digital' and ' library' seem to be in sharp contradiction. Having given some preliminary thoughts to the matter, many philosophers (who should have known better) hastened to conclude that libraries “without shelves" or “without walls" are obsolete. According to their view, libraries are bound to disappear because in the near future we will simply do without them.

Fortunately, the public libraries contuinue to enjoy relatively strong support from governments and the EU. 4 However, in a world which is increasingly governed by transnational corporations, it is not impossible that we will have to witness a period of decadence if not disappearance of public libraries. We already know that the “digitalisation" or the “new technology" can serve as ideological pretexts to the destruction of public service and democratic institutions.

The important question to ask today, is how the role of the library can be further strengthened, and how the information technology may thus be put at the service of democratic society. Information technology and the library do, in fact, have basic function in common, i.e. they both serve as a support for the human memory. After all, the library is an information technology. How to strengthen that information technology?

As a matter of fact, the traditional library with shelves and walls already has adapted to and made its own impress on the digital environment. The development within the public library system of Finland is a striking example. In February 1994, Helsinki city library became the world's first public library on a web server and started, at the same time, to provide public access to the Internet (web, e-mail, etc.) from a handful workstations. 5 Four years later (at the beginning of 1998), all the 35 branches of the city library provided this essential new public service from more than 600 EDP-workstations. In the whole country, the number of libraries providing public access to internet rose from 2 in 1994 to 43 in 1995, 205 in 1996 and 272 in 1997, when it amounted to 60,2 percent of all the public libraries.

During this period, the libraries have also done much good work on the organisation and presentation of the contents of the Internet. Several libraries have made their catalogues of books, journals and other materials available on the web. To some extent the libraries have also got involved in the production of new web-publications on art, literature, cultural history etc. The “virtual library", i.e. the sum of the webpages published by the library are generally of high quality and remarkably sober compared to the commercial hype which came to dominate so much of the Internet during those same years. Not surprisingly, the web pages of the library are also quite popular. In Helsinki, for instance, the number of visits to the library's webpages grew to 2 millions in 1996 and to 3 millions in 1997.

But the real achievement of the library becomes clear only when

we consider the more traditional part of its activity as well. "In practice,

the new has come alongside the old, not displaced it", wrote Maija Berndtson,

the head of Helsinki City library (in its annual report for 1997). During

the four-year period 1994-1997, the figures for “physical" visits and

book-loans remained remarkably stable. The figures for 1997 show that Helsinki

residents visited a library an average of 12.4 times and borrowed an average

of 16.7 works. (“Helsinki's population was 532,053 as at December 1997...

The total number of loans for the City Library was 8,881,658... and the total

number of customer visits was 6,611,822") Library statistics from other cities

show comparable, sometimes even higher

figures6

And the first “virtual public library", the Cable Book

has not faded out in cybespace. On the contrary, while I am writing this

the Cable Book is moving into the newly restored Glass Palace in the center

of the city. Which is good. Let the library have or be buildings, let people

continue to see each others and make use of the common intellectual property

in those public places.

5. The right to information is under imminent threat right here in the information society (appeal)

The right to information is under imminent threat right here

in the information society.

The public libraries, the principle of public access to information, the right to share and communicate knowledge, indeed, the freedom of speech, are threatened. So are the rights of the author, in particular, the moral rights of identification and integrity.

The threat is inherent in the global market economy, which transforms the expressions of the human mind into merchandise, something to be bought and sold, but not to be shared. The threat is not caused by the ongoing, epoch-making digitalisation of information, nor is it caused by the Internet or the great new digital library of its World Wide Web. On the contrary, digital technology allows us both to facilitate access to information and to restrict and control that access. Alas, restriction and control, for the purpose of corporate profit-making, now seem to be taking the lead over the possibility of rebuilding and enlarging our common library.

The threat to the right to information is posed by a combination of ideological and political circumstances:

- the bias of a concept of the information society, which glorifies the information market, but underestimates the role of the creators of the intellectual capital as well as the role of libraries and other public information services;

- the American economic predominance in film, television and popular music, which necessitates a defence of European culture, but does not motivate an attack on library exemptions from copyright and the right of private use of copyrighted materials;

- the weakness and vulnerability of the democratic public sphere in the face of the very market forces that gave rise to it in earlier European history;

- the challenge to our thinking and imagination that is posed by the digital revolution: the need to rethink and redefine "reading", "browsing", "book", "library" and "copy", just to mention some concepts that are unavoidable in a discussion on copyright and the right to information.

The threat is avoidable, the right to information can be reinforced

by legislators and governments, if only the political will to do it is strong

enough. Now is the time to create that political will.

We must act together in order to bring the proposed new EU directive on copyright 7 in harmony with the right to information of all the citizens of Europe. "Save future access to information now!", cries

EBLIDA, the European Bureau of Library and Documentation

Associations, a propos the draft of the new directive. We would all do well

to open our minds to the voice from the library.

8 After all, do we have better specialists

on information than our librarians?

Authors, artists, researchers, journalists and other creators of new information should feel concerned, and involve themselves in the issue of the right to information. On the other hand, as professionals they

urgently need to guard their self-interest. The emerging, already dominant concept of copyright, which puts all essential informational rights squarely in the hands of the "owners of copyright", blurs any

distinction between the author and the merchant. This concern

is indeed eloquently formulated by SACD

9, the Society of Dramatic Authors and

Composers (Paris-Brussels-Montreal), which demands "that literary and artistic

property rights be excluded from the scope of application of MAI" (the

Multilateral Agreement on Investments proposed by the OECD).

Creators, intellectuals, librarians, political and social activists

must unite in a European movement for the right to information.

In democratic society not only authors and scientists, but each individual citizen is, in principle, regarded an autonomous owner and processor of information. Unfortunately, the extended copyrights and intellectual property rights now drafted in the EU-directive and the MAI-agreement would reduce citizens to mere consumers of information., who are only allowed to 'vote with their wallets'. Democracy can only exist if information is shared, that is, owned by the community or by the whole society in its public sphere.

The borders of our common informational ground are threatened by commercial invasion, the very existence of the public domain is at stake.

The public domain, the use of copyrighted materials in the library

and the Internet as a part of the public sphere, must be protected by our

constitutions.

6. Political power to the public library

The political nature of the intellectual property and copyright issues has already been underlined in the preceding notes. These issues need to be lifted onto the agenda of political parties and citizens associations. They belong to the aspects which must not be forgotten when, for instance, trade unions discuss the globalisation of the economy.

It has also been emphasized that the democratic solutions to

intellectual property problems should be sought through the further development

of the public library. The opinion which is commonly held among the library

professionals is that society must strive " [to] ensure freedom of access

to information and knowledge while maintaining a fair balance between the

interests of producers and users regarding copyright and other rights"

10

The notion of a 'fair balance' is a guiding principle; it tells something of the goal as well as of the means. The attainment of the 'fair balance' is almost by necessity a gradual evolution, not a revolution. Still, the transition to "an information society" by necessity implies a change in the political power structure. Considerations on information and democracy in the digitalised information environment may easily lead to reflections on the existing division of power in society.

In many countries, new legislation on the freedom of information is currently under way. 11 The information which is covered by the laws concerning the principle of public access is not copyrighted, nor is it regarded to be intellectual property. Instead, the right of Everyman applies; it belongs to the stuff of which the public domain is made. By principle, this is an area of information where no limits are (or should be) set by private property, but only by strictly defined needs of governmental secrecy, and by the right to privacy of the individual citizen.

Here, again, the library needs to be taken much more into account

than has hitherto been the case. Situated as it is between the state and

the civil society, the public library is particularly well placed to organise

intelligently and to present objectively all the information which should

be governed by the principle of public access. This amounts to giving political

power to the library. And why should the library not be endowed with more

political power than it has had hitherto? After all, this is a question of

division of power. In addition to the Executive, the Legislative, the Judiciary

Powers, and the Fourth power of Press, why should we not have the Fifth,

namely, the Informational Power? Where to invest that power if not in the

public library? And would not the library be the most natural partner for

an Information Commissioner with the powers to order disclosure of information

that an official or a government wants to withold from the public? Where

should the office of an Information Commissioner be situated, if not in the

public library?

Endnotes:

1.

See the related website, http://www.kaapeli.fi/saveaccess

2 My report from the Hourtin

seminar is found at

http://www.kaapeli.fi/book/hourtin.htm 3 i.e. the picture which I have used as an illustration to these notes by making a digital copy is made from the reproduction in Chartier, Roger: Böckernas ordning. Läsare, Författare och bibliotek i Europa från 1300-tal till 1700-tal, Anamma, Göteborg 1995, p 53. 4 See the article The Cable Book and its Knot (1995) at http://www.kaapeli.fi/book/vineart.html

5

Of course, the public or governmental support for the public libraries

varies considerably from country to country. Undoubtedly, the EU takes an

active interest in library development. The Commission has initiated

several projects in this area, see the website of the ECUP+ project

www.kaapeli.fi/eblida/ecup

(section "Projects". Alone, the

"Telematics Libraries Programme" of the Directorate General XIII

comprises over 30 projects).

The actual discussion in the EU parliament is documented in, e.g.

the

Report on the Green Paper on the Role of Libraries in the Modern World,

Committee on Culture, Youth, Education and the Media, which was presented by

by Mrs Mirja Ryynänen MEP 25.6.1998 (A4-0248/98), see

www.lib.hel.fi/syke/english/publications/report.htm

6. Quoted from the annual report

of Helsinki City Library 1997,

http://www.lib.hel.fi/english/annual/

7. Proposal for a Directive

on the Harmonisation of Certain Aspects of Copyright and Related Rights in

the Information Society (10.12.1997),

http://europa.eu.int/comm/dg15/en/intprop/intprop/1100.htm

11. Computers, digitalisation and

online-distribution of documents are explicitely referred to as a motive

for the Finnish reform, i.e. the proposal of the Finnish government (1998)

of a new law on the principle of public access to the activity of the

authorities. (The proposal, in Finnish or Swedish, is found at the website

of the Finnish Parliament,

http://www.eduskunta.fi/ ) In

Britain, the White Paper of the government (Your Right to Know, 1997,

http://foi.democracy.org.uk/)

reveals a comparable development although, interestingly, the "Freedom of

Information Act" which is under preparation there, will be the first of its

kind. The British Government's White Paper also proposes the appointment

of an Information Commissioner with powers to order disclosure of information.

Freedom of information, the realisation of the principle of public access,

is a hot subject of debate in England, see the website of the Campaign

for Freedom of Information,

http://www.cfoi.org.uk/.

|