|

|

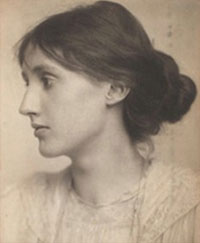

page three TODD BAESEN: The longest poem in the book is Birds of Iraq, which alternates viewpoints between the bombing of Iraq and Virginia Woolf.

PATTI SMITH: I remember quite well when I started working on that poem. It was around March 18th and there was a full moon out that night. I started thinking about it then and started writing it on the first day of spring, March 20th. I woke up that morning and the Americans had just invaded Iraq. We had gone into Baghdad and the TV was on and I could hear the news, and I could also hear the birds chirping outside my window and I wondered if the birds were chirping in Iraq on the first day of spring, while we were bombing them. This thought kept looping through my mind. But I also had this really terrible migraine. Getting migraines is really a nightmare, because they can go on for 18 hours. You really have to stay centered or else you’ll go mad. So one of the things I did to keep my sanity while I had this migraine was to work on this poem. At the time I was thinking of a couple of different things. First, the news reports kept filtering in, and also my mother’s birthday had just passed, and my mother used to get these horrible migraines as well. So I was thinking about my mother and I was also thinking about Virginia Woolf, who also got these migraines, but for three weeks at a time. So I thought, “I’m really lucky, because this is only going to last 18 hours, so it will only last as long as a flight to Japan.” Then sometime afterwards, I was talking to a journalist who was imbedded with the soldiers in Iraq, and I asked him what it was like that day. He said, “It was the strangest thing. They have millions of these little sparrow-like birds in Baghdad and you always hear them chirping, but on that day the birds were silent. They could feel it coming. So that’s how I writ Birds of Iraq. TODD

BAESEN: Birds of Iraq actually alternates between four different viewpoints:

Virginia Woolf, your mother, yourself, and the invasion of Iraq. I just hope that

George Bush is going to have a continuous migraine for starting such a completely

unnecessary conflict. But knowing that background really helps the reader get

a fuller appreciation of the poem, as do these excerpts from an earlier version

you read in Charleston, England, at the 2003 Virginia Woolf festival: Never

knowing why she grasped the sheets and twisted it with her slender hands * * * * * And she couldn't write Are

there birds singing in Iraq? TODD BAESEN: Auguries of Innocence is actually your first book of poems since Early Work came out in 1994. PATTI SMITH: Well, Early Work was a compilation I put together of work I did in the seventies. I did write The Coral Sea (1996), which was prose poems for my friend Robert Mapplethorpe, but Auguries of Innocence is my first book of published poems really, since 1979. TODD BAESEN: Since it's been over ten years since Early Work, I'm wondering if writing a poem takes a long time for you, as it did for Sebastian, the gay poet in Tennessee Williams Suddenly, Last Summer? It took him nine months to finish a single poem - "the length of a pregnancy." PATTI SMITH: Actually most of the poems in the book are fairly new. I have a lot of unpublished poetry, but almost all of these poems were written in the past year or so, except for a couple of them. The Writer's Song I wrote in the eighties, and Written by A Lake is about ten years old. But most of them are quite recent. In fact, there's a very simple one, called Three Windows that is probably the last one I wrote before the book was published. I wrote it in St. Peter's Square the night John Paul II died in April of 2005. I was standing in the square and there were thousands of people there and I was told that these three lighted windows was where John Paul II was lying in his compartment, and that when the lights went out in the windows, that meant he had died. So I wrote the poem when the lights went out. TODD BAESEN: You also wrote the title track to your album Wave, when Pope John Paul the first passed away in 1978. PATTI SMITH: Yes, I had seen John Paul I on TV and there was just something about him that seemed truly beautiful. He seemed like a truly pastoral man. He really exemplified and radiated Christ's teachings, in their best form and unfortunately he died only 33 days after he became Pope. So I wrote Wave for him and what it was about, was me imagining I'm walking along the beach and who do I see walking on the beach but my favorite Pope. TODD BAESEN: You mentioned Written By A Lake being ten years old, and I believe you debuted the poem

here in San Francisco. TODD BAESEN: If you hadn't gotten the manuscript back we could have probably reconstructed it from a bootleg tape. PATTI SMITH: Oh, that could have been helpful. Here is Patti's original version of Written By A Lake, as she performed it in San Francisco on March 18, 1996: Written By A Lake (1996 version) New Year's Day. Rain. Two white candles illuminate the room. This is where they sleep. He writes. She confesses. This is where she weeps. She is the cause of the rain. She would not stop weeping and the sky obliged to follow, did. How is that mapped out? What is the refrain? Why must the sky follow? Is the heart hollow? Sinking in the center of a bottomless lake. An eye with time as her lashes. Pretty vain pool. The heart plunges merrily. It is deceptive. How light it appears. Yet in truth how weighty a thing. This powerful stone carved in the shape of an organ with chambers pumping. How slick a shadow it leaks as its signature. Sticky ox-blood the color of new shoes. High topped, golden-laced and donned with such expectations as to ride out life on horseback. Racing from hill to hill with humor, horror, bits of English, Spanish stitched in sleeves. Look you radiant wash yard. The sheets billow. The wet folds tell these stories. Once there was a girl who walked straight, but she was truly lame. She walked upright in new boots, yet I tell you her feet were bare. She walked and she lived forever. Yet there she is, buried in a vault of fertile air. And if he, slipping at last should rest his head against the glass, releasing beads of warm spittle from his sleeping mouth, parting as if to speak. And if she, shaken from her torpor, should rise to write, what would she write? It is nothing. These fragments. Soft as ash are nothing. Signs for want of blood. For here, blood is composed of sorrow. A wound is the temple your fingers press. The door well, naked, triggering a spring exposing the hard corner from where you walk. Had you stumbled, offering a palm encasing rivets extracted from the wet pallet of this time or that. Had you pricked the hour's hand, one would have said with nothing but eyes, think nothing of it. For what remains to flush is nothing save salt jamming the mechanism of formal delights, former misery. Nothing save salt to form in a mound. A bundle to fling over a shoulder. And would you be bitter? Or would you think nothing of it? And some years later would you toss rivets like dice across a board of dampness and grass? And would you sit upon a ledge of stones circling a low glowing body unfastening the dressings of a gone burden. The cremation of all my sorrow-spread the grains with your fingers and without thought brush them aside upon a board of glass. Thus free to drown in sorrows of your own. Immerse yourself in a stillness flanked by translucent hills, one a mound that serves the people as a mountain-coated, immaculate wreathed at the throat with beads of cloud. These things were written by the lake. Do not grip a sword, nor draw what might be drawn for wisdom is a dying bird, encased in a palm. A roving eye nestled in a cheek, pure as yourself. Next to nothing. These things were written by the lake. That is to say before existence as existence was scripted and dealt. A pack of lives. Each with a winning face, each with this blushing command: Prick

this. This moment the hand is free |

|